Introduction

Many U.S. homeowners are surprised to see their monthly mortgage payment change—even when they have a fixed interest rate. While fixed-rate mortgages lock in principal and interest, escrowed costs such as property taxes and homeowners insurance can fluctuate over time, causing payment adjustments.

According to consumer research published by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), escrow-related changes are one of the most common sources of confusion and payment shock for homeowners, particularly in the first few years after purchase. These changes are not discretionary; they are governed by federal servicing rules and local tax and insurance realities.

This article provides a neutral, educational, U.S.-specific explanation of how escrow accounts work, why payments change, and what public data shows about the underlying cost drivers. It does not provide advice, inducements, or recommendations.

What Is an Escrow Account?

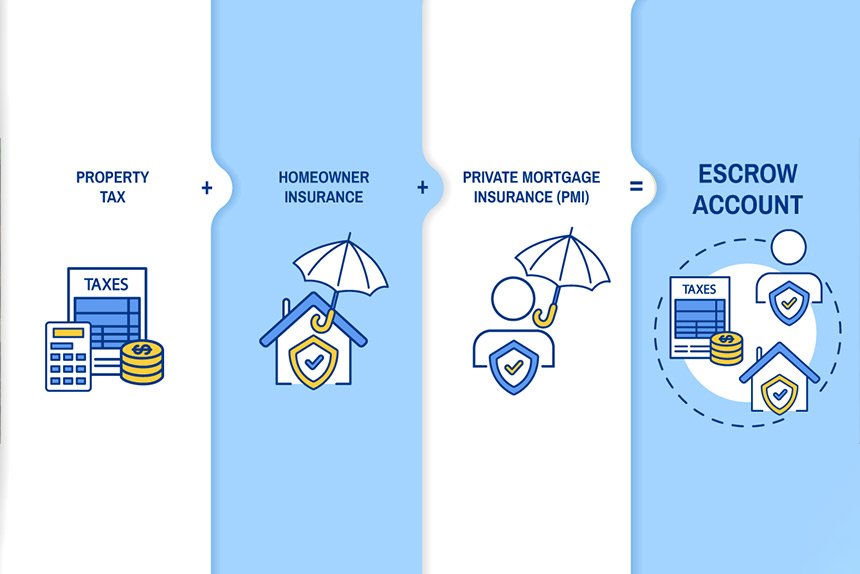

In U.S. mortgage servicing, an escrow account (sometimes called an impound account) is a separate account maintained by the loan servicer to pay certain property-related expenses on behalf of the homeowner.

Escrow accounts typically cover:

- Property taxes

- Homeowners insurance premiums

- Flood insurance (if applicable)

Funds are collected monthly as part of the mortgage payment and disbursed when bills come due.

Why Escrow Accounts Exist

Escrow accounts serve several purposes:

- Ensure timely payment of taxes and insurance

- Protect the lender’s collateral (the property)

- Reduce the risk of tax liens or uninsured losses

According to the CFPB, escrow accounts are commonly required for loans with:

- Higher loan-to-value ratios

- Government-backed insurance or guarantees

- Certain investor or servicing guidelines

Not all mortgages require escrow, but many do.

Fixed Mortgage vs. Variable Escrow Costs

A common misconception is that a “fixed mortgage payment” never changes. In reality:

- Principal and interest may be fixed

- Escrow components are variable

This distinction explains why homeowners may experience payment changes even without refinancing.

The Components of Escrow Payments

Property Taxes

Property taxes are assessed by:

- Counties

- Cities

- School districts

- Special taxing authorities

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the median annual property tax bill for owner-occupied homes is approximately $2,690, but bills vary widely by location.

Reassessments, millage changes, or voter-approved levies can increase taxes year to year.

Homeowners Insurance

Insurance premiums reflect:

- Replacement cost

- Local risk factors (weather, wildfire, flood)

- Claims experience

- Reinsurance costs

Data summarized by the Insurance Information Institute shows that:

- National average premiums are roughly $1,400–$1,700 annually

- High-risk states (e.g., Florida, Louisiana, California) often exceed $2,400–$3,000

Premium increases directly affect escrow requirements.

How Escrow Amounts Are Calculated

Initial Escrow Setup

At closing, servicers estimate:

- Upcoming tax bills

- Insurance premiums

They collect:

- Monthly escrow payments

- An escrow cushion, allowed under federal law

The Escrow Cushion

Under Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA):

- Servicers may maintain a cushion of up to two months of escrow payments

- The cushion helps prevent shortfalls if costs rise

This cushion is often misunderstood as an extra fee; it is a regulatory allowance.

Escrow Analysis: Why Adjustments Occur

Servicers perform an annual escrow analysis to compare:

- Amount collected

- Amount paid out

- Expected future costs

If a mismatch occurs, one of three outcomes results:

- Shortage: not enough funds collected

- Deficiency: negative balance

- Surplus: excess funds

Each outcome has specific handling rules under RESPA.

Payment Increases Explained

Escrow Shortages

A shortage occurs when actual bills exceed projections. The servicer may:

- Spread the shortage across 12 months

- Increase the monthly escrow payment

This often results in a noticeable payment increase.

Rising Taxes or Insurance

Escrow payments increase when:

- Property tax assessments rise

- Insurance premiums increase

- New insurance requirements apply (e.g., flood coverage)

These changes are driven by external factors, not servicer discretion.

Why Changes Often Happen in the First Year

CFPB research shows that escrow payment changes are most common:

- Within the first 12–24 months after purchase

Reasons include:

- Initial tax estimates based on prior owner assessments

- Post-sale reassessments at market value

- Insurance repricing after underwriting review

First-year payment shock is a well-documented pattern.

Regional Differences in Escrow Volatility

Escrow volatility varies by location due to:

- Frequency of property tax reassessment

- Disaster risk exposure

- Insurance market stability

For example:

- States with annual reassessments experience more frequent tax changes

- Disaster-prone regions face higher insurance volatility

This explains why payment stability differs across markets.

Escrow vs. Non-Escrow Loans (High-Level)

Some homeowners choose loans without escrow, paying taxes and insurance directly. In those cases:

- Monthly mortgage payments remain stable

- Tax and insurance bills are paid separately

- Payment shock still occurs—just outside the mortgage bill

This article does not evaluate or recommend escrow choices.

Escrow and Affordability Metrics

Housing affordability studies by the Federal Reserve emphasize:

- Total housing cost matters more than mortgage rate

- Escrowed increases can materially affect cash flow

This is why affordability calculators that exclude taxes and insurance may understate true cost.

Common Misunderstandings About Escrow

“My Lender Raised My Rate”

Escrow changes do not affect interest rates.

“The Servicer Made a Mistake”

Most changes reflect updated tax or insurance bills, not errors.

“Escrow Is Optional Everywhere”

Escrow requirements vary by loan type and lender guidelines.

Consumer Protections and Transparency

Under RESPA and CFPB servicing rules:

- Borrowers must receive an annual escrow statement

- Statements must explain shortages or surpluses

- Surpluses above a threshold must be refunded

These rules are designed to provide transparency, not to eliminate variability.

Long-Term Escrow Trends

Over time, escrow payments tend to rise due to:

- Property value appreciation

- Insurance cost inflation

- Local government budget changes

According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, housing-related costs have risen faster than general inflation in recent years.

Why Escrow Education Matters

CFPB surveys indicate that many homeowners:

- Expect fixed payments to remain constant indefinitely

- Are unprepared for escrow-driven increases

Understanding escrow mechanics helps contextualize these changes as systemic rather than arbitrary.

Summary: A U.S. Data-Based Perspective

From a U.S. consumer education standpoint:

- Escrow accounts collect taxes and insurance, not interest

- Payments change due to external cost increases

- Annual escrow analyses adjust for real expenses

- First-year payment changes are common

- Regional factors drive volatility

Escrow accounts are administrative tools governed by law, not discretionary pricing mechanisms.

Author Information

Written by:

Asim Iftikhar — Real Estate Contributor, ACT Global Media

Editorial Disclosure

This article is provided for general informational purposes only and does not constitute real estate, mortgage, financial, legal, or tax advice.

Regulatory Notice

Escrow practices, tax assessments, and insurance premiums vary by jurisdiction and individual circumstances. Information is based on publicly available U.S. sources